First published in The Jakarta Post, August 30, 2006

First published in The Jakarta Post, August 30, 2006JACKLEVYN FRITS MANUPUTTY: PROMOTING RECONCILIATION AMONG MALUKU PEOPLE

Alpha Amirrachman, Contributor, Ambon, Maluku

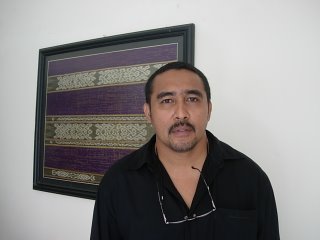

Jacklevyn "Jacky" Frits Manuputty is well-built, which gives him the appearance of an athlete rather than a Protestant priest.

But he is no mere priest who preaches from an ivory tower; he is also an energetic social activist who has traveled to remote parts of Maluku and other regions of Indonesia to feel for himself the grassroots pulse.

His travels and dialogs with people from a variety of religious and ethnic backgrounds, especially with those marginalized by the march of modernity like poor fishermen or farmers, has bolstered his awareness, not only of acute social problems but also the wide diversity of people in this country.

His sensitivity toward diversity and its related challenges developed a long time ago. Born on July 20, 1965, in Christian Haruku village, Haruku island, Central Maluku, young Jacky often accompanied his uncle, an upu latu (village chief), who visited neighboring Muslim Rohomoni village, both in official and informal capacities, to strengthen relations between the two communities.

In Maluku tradition, his mother's fam of Ririmase (Christianity) is believed to have the same genealogy as the fam of Sangaji (Islam) under the soa of Mone. The soa is an institutionalized tradition that oversees several fam believed to have the same genealogy.

"So we visit each other, not only on religious holidays such as Idul Fitri and Christmas, but also for family events such as weddings or get-togethers when one of our children is due to go to a new school and needs help," he said during a recent interworking group visit forum in Ambon organized by the International Center for Islam and Pluralism (ICIP) in collaboration with the European Commission.

The forum was attended by peacemakers from other troublespots, Poso and Pontianak.

"I'm affectionately referred to as `Abang Imam' by Muslim families," he said, smiling.

However, he began to feel the silent tension between the two communities while still at senior high school in Ambon. The competition for the leadership of OSIS (a student organization), for instance, was colored by religious overtones.

Students became polarized by mostly two ibadah (prayer) groups of Christians and Muslims that gradually sowed the seeds of mutual suspicion and prejudice.

That is the point in his life at which he became aware that enhancing the spirit of brotherhood between religious communities is a continuous process and, if not managed carefully, could become a time bomb that could explode and destroy them.

He decided to become a priest because he believes religion plays an important role in Maluku society and people still listen to their religious leaders.

He studied at the Driyarkara School of Theology and Philosophy in Jakarta and later served as a priest in Haria village in Saparua island, Maluku.

He recalled that he and his wife were about to visit Muslim relatives

at Idul Fitri in Batu Merah district when an altercation between a public minivan driver and a passenger later escalated into massive violence in and around Ambon on Jan. 19, 1999.

"There was a mass mobilization and polarization of people in just one day," he said, recalling his bewilderment. Muslims were identified by white ribbons, Christians red.

"Agents provocateurs could be found in both Muslim and Christian areas. In a Muslim area of Waihong, a man with a military haircut stood on a jeep shouting about separatism. In Christian areas a message on the need to expel BBM (Buton, Bugis and Makassar) ethnic groups -- often migrant Muslims -- spread fast."

Massive and bloody violence was inevitable. Thousands were murdered without mercy; many were trapped helplessly in the archipelagic province.

Kidnaping, lynching and mutilation were carried out with ritual fervor. Even the sea in Maluku became a mass grave, which deterred people from eating fish for years. Fear and brutality became everyday realities.

After years of sporadic effort, "I felt ashamed that much of the reconciliation was initiated by outsiders," Jacky said, referring to a bakubae movement that he blasted as "workshop-to-workshop forums in Java" that did little to take account of local circumstances and traditions.

After publicly signing up to the historic Malino II peace agreement, Jacky and his colleagues from the Protestant Church of Maluku (GPM), where he served as secretary at its crisis center, the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) of Maluku and the Diocese of Ambon established an organization known as the Maluku Interfaith Institution for Humanitarian Action (ELALEM) in December 2003.

"Most of the responsibility rests on the shoulders of Maluku people," he declared. Jacky was unanimously elected as its director by the board.

During its first year, ELALEM provided a forum for people to discuss their ideas on how to solve Maluku's social problems and find the realistic means to address them. This involved students, politicians, journalists, religious figures and intellectuals.

His travels and meetings with communities in Maluku and people as far afield as Lembah Baliem, Papua; Musi River, Kalimantan; and Waduk Gajah Mungkur, Central Java, have inspired him to adopt two crucial themes for the organization: economy and education.

With support from the United Nations Development Program ELALEM aims to raise the quality of social, cultural and economic life to demonstrate the spirit of survival of Maluku's religious communities.

ELALEM programs include institutional capacity-building, developing positive public perceptions and building a network of pluralism observers to promote peace and community empowerment.

In the economic sector, ELALEM has assisted the local government to draw up an economic plan for several villages, especially those on the coast.

In collaboration with the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and local governments, ELALEM organized a technical cooperation project called Reintegration Support through Rebuilding Communities, which has three basic pillars: economy, social life and security.

In the education sector, ELALEM produces movies that carry cultural messages to be distributed to students and, together with the local government and education experts from Pattimura University, has developed a peace curriculum.

A group of teachers from pilot schools have just been trained in the curriculum. For counseling, ELALEM has trained facilitators for three districts: Baguala, Sirimau and Nusa Niwe.

ELALEM has also called on Christian and Muslim figures to find agreement on what are called peace sermons. These figures have agreed to using peace messages during their sermons in their respective communities.

Jacky, who also teaches Western philosophy at the Indonesian Christian University of Maluku (UKIM), has traveled extensively -- to the U.S., Sri Lanka, Australia, France, Holland, Switzerland, Belgium, Britain, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines -- to share his experiences at a number of forums.

Nevertheless, this has not been without challenges. During the conflict, his parents' house was burned down by a mob of fanatics who accused him of being a collaborator. Luckily no one hurt.

Jacky has no regrets: "It was just part of the struggle," he said.

http://www.geocities.com/batoegajah/jp040906c.htm