First published in The

First published in The NEIGHBORS RI, AUSTRALIA MUST LEARN TO LIVE TOGETHER

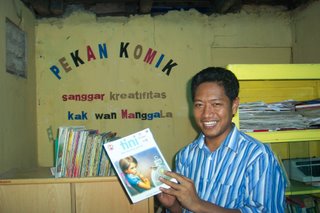

Alpha Amirrachman, Serang, Banten

The love-hate relationship between

Bizarrely for many Indonesians, the Australian government reiterated its support for

Such perceived "double standards" are certainly hard to digest for many Indonesians, particularly for the nationalists who are increasingly sure that relations with the "double-faced" Australia will only disturb Indonesia's international standing, and therefore strongly urge the government to cut diplomatic ties with the country.

Bear in mind that

Thus, the recalling of Indonesia's ambassador to Australia might have been a blunder, with the impulsive Vice President Jusuf Kalla trying to play hardball with Australia by demanding that the country provide an "adequate" explanation before Indonesia could send back its ambassador.

What seems certain is that after building up so much social capital,

During the authoritarian New Order regime, for

The way

And with members of both governments showing displeasure over disdainful cartoons printed by the free media in both countries, the two neighbors likewise need to be aware of the pressing need for relations to be mutually inclusive, not mutually exclusive. For jingoists in the two countries, the proximity of the two might be a bitter fact -- but it is morally inescapable.

Thus, building relations based on the spirit of heartfelt neighborliness is the dignified choice, if we are to have productive and lasting relations. It is not always easy; indeed, nationalistic sentiments and feelings of superiority might always lure the politicians to put the relationship to the test, sparking undue political fire.

Even in day-to-day life, relations between neighbors are not always genuine, unless there is a specifically emotional interest that truly binds us. We might feel that we need to be kind to our closest neighbors on the mere grounds that they will at least phone us if they see trespassers in our yard.

But if we have strained relations with our immediate neighbors, though putting on a straight face, we will still feel uncomfortable when walking out of our house. An unpleasant way to start the day, isn't it? The comical thing is that we might not need a third party to help mend our strained relations, as at the end of the day we will all realize that no one benefits from this furor.

The writer is an alumnus of